"IT'S TIME TO TAKE

THE 'COMIC' OUT OF

COMIC BOOK!"

© 1983 Trip ReynoldsAt the conclusion of this 1983 editorial follows an epilogue from 2000 and a current update for 2024.

Background

I grew up reading comics. Yeah, I know, you've heard that before. As a collector and fan for more than 25 years, I've acquired a considerable amount of knowledgeable about the comic book industry. Shortly, I'll be entering my thirties and I think it's appropriate to reflect on my life as a collector and my personal collection of 7,000 books [in 1983; 32,500 in 1999]. However, I will provide, in particular, commentary on the future of the comic book industry.

.

Profile

When you're a kid, still in grade school (or maybe even high school), it's more or less socially acceptable to read comics -- or as my parents' generation would call them: "funny books". Seven years ago, I would never have read comics at work. Afterall, I work in a briefcase-carrying, very professional, business atmosphere. Understandably, creating the wrong impression can be politically detrimental to career success. As a sophisticated, young, 29-year old professional with typical business and social contacts, it's difficult explaining to your peers that you collect, and even read, comic books. The looks and stares you get sometimes.' I remember thinking, "Well damn, did I commit a crime? Did I kill somebody?"

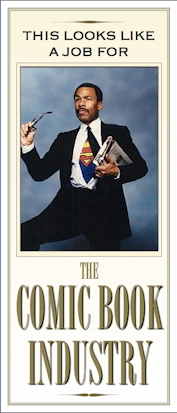

Well, for three years now, I haven't been so apprehensive about letting friends, or anybody else) know that I collect, and actually read, comics. To coin a phrase: "I'm out of the closet!" I refuse to be intimidated anymore. I want people to know how good (some, but not all) comics are. As a free lance artist and illustrator, I also enjoy drawing comics, creating my own characters and stories and, hopefully, one day achieving commercial publication.

| MY ART? | MY "GRAPHIC BOOK" | |

Plus, portrait art, photography, and videography. |

Blackgod © 1972 Trip Reynolds |

|

WHY DIDN'T I PURSUE A CAREER IN ART? |

||

MY ARTISTIC ICONS: I'm not particularly fond of contemporary art or artists, primarily because much of their work I do not consider challenging or of interest. As far as artistic periods, the "Baroque" period is my favorite, and master Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio is my favorite artist of this period. However, without a doubt the most creative, most imaginative, most technically proficient, and most talented artists - period - are contemporary comic book and graphic artists such as Frank Frazetta, John Bolton, Richard Corben, Bernie Wrightson, Boris Vallejo and Julie Bell, Jim Steranko, Jim Starlin, Paul Gulacy, and especially Gene Colan and Jack Kirby. Collectively, their work is without peer! |

||

The fact of the matter is, with the majority of story lines anchored to science fiction concepts and principles, most adults don't realize the term "comic" has nothing to do with most mainstream "comic books." There's nothing "funny" about most comic books. As a self-appointed, independent, goodwill ambassador for the comic book industry, I hope to make people recognize the value of comics as an entertainment vehicle that successfully combines the written word and the "story-telling" illustration.

The Collector

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Record Keeping

Do you realize how much space approximately 7,000 comic books takes up? Luckily, I'm a very organized and pragmatic person. I don't just have comic books dumped in a room. I've created a library consisting of comic books. My record keeping system is simple, efficient and accurate. In the near future I'll be converting my manual records to a home computer data base. Hi-tech is definitely here.

Howard Zimmerman, Editor-in-Chief of Comics Scene Magazine said in a September 1983 editorial, ". . . there was a time not too long ago when I (used) to buy every book that is published every month." While close, my comic book purchasing habits are not quite that aggressive. Yet, I am easily a favorite customer for most comic book specialty stores. Below is a snap shot of comic books expenses for the first half of 1983.

January February March April May June July Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Average Weekly Monthly Total Year-to-Date Note: The average cover price for "regular" Marvel comic book in 1983 was 60¢. I typically purchased thirty-(30) titles for a weekly averaged cost of $21.17 and a monthly average cost that ranged from $100 to $150.00. Conversely, the current 2024 price for a "regular" Marvel comic book is $4.99. In 2024, the purchase of 30 titles would average $149.70 per week, $598.80 per month, and $7,185.60 per year.

Undeniably, some of you out there in "comic-book-dom" can't imagine how in the world I can spend so much money on comics, stay current in reading all titles. and still have time to eat, breath, work and do whatever else comes up. Honestly, I do read everything, but not right away. I shift around frequently. Consequently, I might be current in 20 titles, and at the same time be a year or more behind in 20 other titles. But all in all I know what's going on.My primary reason for providing the aforementioned background, profile and overview of my collecting is to, hopefully, demonstrate to the major publishers, artists and writers, that my comments, and those of my peers, should be taken seriously. Which brings me to what some of you will probably feel is a rather abrasive and highly critical analysis of contemporary comic book publishing.

.

Commentary

For some time now, the comic book industry has been throwing around figures on how comics are being read by a progressively older audience. Supposedly, approximately fifty percent of all comic books are purchased by persons between 15 and 25 years of age, predominantly male. While this is probably true, I think this statistic requires further analysis and interpretation.

There was a time, and not too long ago, when the major publishers of comic books created their product primarily to attract an audience of 10-12 year olds. If you look at the current condition of mainstream comics it is apparent that to some degree this marketing concept still persists. True, the overall quality of writing and art is nowhere near as pre-adolescent as it was 15-20 years ago; but we still have books like GI Joe, US 1, Superboy, Captain Carrot, Team America, DNAgents and others.

I think that Marvel, DC and the independents (like Pacific Comics, Eclipse, First, etc.) are generally on the right track by attempting to publish books geared toward a young adult and older audience. The development of the "Graphic Novel", and the use of better quality paper for books like Camelot 3000, Marvel Fanfare, Twisted Tales and others, hopefully will pave the way for the next genesis in comic book publishing. Unfortunately, format and substance changes come much too slowly in the comic book industry. The industry has not kept pace with society. It appears as though the comic book publishers have been in the "Marvel Universe" or on "Earth One, Two or Three" for so long that no one thought to look out their window to see what is happening in the real world. Publishing "comic" books geared for the pre-adolescent market should be, at best, minimal. Particularly, when as reported in the March 1983 issue of Money Magazine:

- Except for the population boom in the southwest United States, most elementary, junior high and high schools across the country have been and are continuing to experience declining enrollments.

- Nearly one-third of the current US population was born in the post-war (World War II) baby boom (from 1946-1964).

- One-third of the US population is currently between 19 and 37 years of age.

- By 1990, one-third of the US population will be aged 25-44 years of age.

According to the US Census Bureau, all available data confirms that the US population is getting older. How long will the comic book industry continue to ignore the single greatest and fastest growing consumer market? Do you know what audience the television networks, radio stations, motion picture studios, fast food restaurants and convenience food stores all compete for? That's right: the 18-39 year old, adult, audience. Why? Because as a group, it is generally the most mobile, working (with the greatest amount of disposable income) and educated.

I think that a working adult is much more likely to be able to afford the X-Men graphic novel than some 12 year old. True, 12 year olds do not have car notes, mortgage payments, credit cards and bills, bills, bills. Adolescents can, and some do, spend a substantial portion of their available income on comics. However, an adult can make a much stronger financial commitment towards the regular purchase and/or collecting of comic books. Keep in mind that I spend from $1,500 to $2,000 a year [in 1983] on comic books, and I've got a car note, mortgage payments and so forth and so on - like most adults do. I'm not the only 29 year old out here who purchases/collects comic books. Believe that!

What the comic book industry should, and must, do is create the kind of product that caters to the interests of adults. The use of words and pictures in a storyboard format does not have to be perceived as juvenile. Even though historically, most adults have acquired this perspective of comic books. Yes, I'm not only talking about the redirection of the comic book industry, but also, the re-education of America about comic books.

I'm not the only one who is dissatisfied with the current state of mainstream comics. As reported in the March 1983 edition of Heavy Metal Magazine, many professionals within the comic book industry have made some rather adverse commentary:

Will Eisner: "What's wrong with comics? Nothing! -- THANK GOD NO ONE ASKED ME WHAT'S WRONG WITH COMIC BOOK ARTISTS, WRITERS AND PUBLISHERS!"

Kim Thompson: "The American comic book is a zombie. And the world laughs at it..."

Ted White: "Today's comics consist of interminable episodes of never ending epics, written by former fans who never learned how to tell concise stories. And only superhero comics are left, giving the field a single, narrow, self-indulgent focus."

Walt Simonson: ". . . Comics are too cheap. . . . A cheaply made, cheaply sold item is neither respected nor respectable in a modern society such as ours."

Pete Hamill: "They (comics) need executives who will take risks. They need to attract writers and artists from other fields. . . . Where is the Fellini of comics? The Woody Allen? The Francis Coppola? Out there, somewhere over the next hill, waiting for a chance."

IDEAS1. Format

It is not necessary to publish 40 zillion titles in order to make a buck. Most importantly, it is not cost efficient to publish so many individual titles. For example, instead of Marvel publishing Thor, Ironman, The Fantastic Four and The Avengers separately for 6O¢ each (22 pages of art), I would much prefer to purchase one magazine, either in the Epic Illustrated format, size and paper or in the Marvel Fanfare format, size and paper, with a minimum of 88 pages of art. In dollars and cents: instead of paying $2.40 for four titles on poor quality paper, I'd prefer paying $3.OO-$3.50+ for one monthly "graphic magazine" on good paper.

In the July 1983 issue of the printing industry's trade publication, Printing Impressions, Fred G. Phillips reports, "Marketing the product [comic books] has become a problem, and that reflects back on the slight drop in printing orders (from 750 million in previous years to about 400 to 450 million currently). Newsstands make more money allocating space to a magazine that will sell for $3.00 than one which sells for 6O¢." In the same article, Dick Hartman, World Color Press Vice-President of Corporate Operation, and manager of the Sparta, Illinois division where 90-95% of all comic books are printed, said, "Our normal print run on a single book is about 32 pages and 200,000 copies. The printing process is very dirty and has all of the problems associated with the old newspaper printing process. I don't encourage any printer to get into the comic printing business." Apparently, even printing industry professionals feel that the current format and printing process for comics is both antiquated and not commercial.

So, comic book publishers, why not seriously consider changing the standardized comic book format?

Disadvantages

- Compiling several titles into one publication, using better paper, is going to cost more and may result in plummeting sales.

- Some readers are not going to like the assortment of titles combined into one publication

and accordingly may decide not to purchase the magazine.Advantages

- Image: A comic book formatted like Epic Illustrated would have a much classier look and could appeal to a much more mature and literate audience.

- A classier, more sophisticated publication could contain a greater diversity of advertisers. Generally, if a magazine has a diversity of advertisers it also has an equally diverse audience. This translates into greater revenue potential for the comic book companies, which further translates into more money available to produce a better product.

- A higher cover price could be charged to produce additional revenue potential for the comic book companies.

- By combining several titles, persons who buy the magazine for one or two specific titles will be exposed to other titles which they would not normally buy or read.

- Let's say then that the norm is to combine four titles into one book. Here are several options:

1. The assorted titles of each magazine become "permanent" to one magazine, i.e. Green Lantern, Teen Titans, Supergirl and Justice League of America in one magazine. Thor, The Avengers, Iron Man and Alpha Flight in another. Ms. Mystic, Twisted Tales, Captain Victory and Elric in a third, and so on.

2. The assorted titles could shift routinely, or periodically, from one magazine to another.

3. For really "hot" titles like the X-Men and the Teen Titans, change the format to include what would now be considered 4-6 issues of the same title into one single issue released quarterly or bi-annually. This action could help to improve quality, relieve some of the deadline pressure on the writers, artists and printers, and at the same time develop a feeling of continuity, loyalty and involvement for the reader. For instance, instead of publishing six (6) X-Men or Teen Titans during the course of the year for the current 6O¢ each ($3.60 total), publish all 6 regular monthly editions in one "graphic novel" volume on good paper for $4.95-$7.O0. Each release of these books would be heralded as a media event. Marvel and DC, you do know how to market don't you? If not, take a clue from the very successful film marketing and promotion divisions of your parent companies (i.e., Warner Bros., and New Line, respectively.)

4. The opportunity to develop new audiences within the largest segment of the population would provide for continued growth and security in the industry for the future.

2. Explore and Develop New Products

We should all realize that at one time or another, most adults have read comics. As 'we get older and take on adult responsibilities, comic books have traditionally become a non-essential. Afterall, only kids read comics, right? So, for many adults over 25 years of age, it's probably been a long time since they have read a comic book - unless they are already a comic book enthusiast, like me) or a parent that religiously escorts their children to the local comic book specialty store.

Question: How can the comic book companies recapture a "lost" adult audience and create new adult audiences?

I like superheroes, science fiction, fantasy and horror stories, but of course, the same is not true for everyone. The superhero "sameness" that is pervasive in mainstream comics has practically saturated the industry into mediocrity. What the comic book companies should do is explore the "graphic" illustration of all kinds of literature. Realistic tie-ins do exist with other media. For example presented below is the New York Times Best Sellers list for fiction as of August 7, 1983.

(Title - Writer - Story)

THE NAME OF THE ROSE - by Umberto Eco - Unraveling the mystery of a murder in a 14th-century Italian monastery.

RETURN OF THE JEDI - Adapted by Joan D. Vinge - Profusely illustrated storybook based on the latest "Star Wars" film. Tied with "The Name of the Rose"

THE LITTLE DRUMMER GIRL - by John le Carré - A British actress caught between Israeli intelligence agents and P.L.O. terrorists.

GODPLAYER - by Robin Cook - The marriage of two physicians crumbles as death stalks their hospital's corridors.

THE SEDUCTION OF PETER - by Lawrence Sanders - The sudden, danger-filled success of a long out-of-work actor.

HEARTBURN - by Nora Ephron - A romance novel about adultery, revenge, group therapy, pot roast and a marriage breaking up.

CHRISTINE - by Stephen King - A car that kills is at large among a Pennsylvania town's high school set.

HOLLYWOOD WIVES - by Jackie Collins - The struggle for money and power in Tinsel Town

THE SUMMER OF KATYA - by Trevanian - A love story with dark family secrets, set in France before World War I

WHITE GOLD WIELDER - by Stephen R. Donaldson - Book Three of "The Second Chronicles of Thomas Covenant," a fantasy saga.

Why don't the comic book companies attempt the serious adaptation of best selling novels? These truly "graphic novels" should be marketed at finer book stores and comic book specialty stores, and should receive the same kind of first class publicity campaign which is now standard for best selling books, feature films and new products.

Imagine, then, that the next Robert Ludlum, Norman Mailer, John Updike, Herman Wouk, James Michener, Stephen King, Arthur C. Clarke, Robert H. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov or Ray Bradbury novel is not published in the traditional straight print format, but instead is published exclusively in the "graphic novel" format. If executed as I envision it, this publishing strategy could provide the necessary image of maturity and sophistication which will recapture and create new adult audiences. Readers would no longer have to wait for the movie to be adapted from the novel in order to visualize action, characters, atmosphere and all the other ingredients that when combined form a story. Wouldn't it be an interesting twist to see motion picture studios doing adaptations of graphic novels, instead of comic book publishers doing adaptations of motion pictures?

Maybe Jim Starlin could illustrate the next Arthur C. Clarke novel? Maybe Marshall Rogers could illustrate the next Robert Ludlum novel? Get the idea?

.

3. Product Distribution

Immediately curtail and ultimately discontinue the distribution and sale of comic books in grocery stores, drug stores and at newspaper stands. The future of the comic book industry rests solely in the hands of comic book specialty stores and in other commercial outlets, such as finer book stores which exclusively sell reading material. Newspaper stands and comic book racks are an antiquated method to market comic books.

Often - no, routinely - these stands and racks are cluttered and unkept. In many instances newspaper stand operators take an indifferent attitude toward prominently displaying comic books among what they feel are their more 'legitimate" money-making magazines. Most importantly, it is difficult to collect each issue of a title due to occasional distribution interruptions.

Quoting from Bill Overstreet's 1982 Comic Book Price Guide Update, "Marvel Comics Group has reported that 40% of their sales and 70% of their profit is in the specialty shop market." With comic book specialty stores becoming so popular and successful, maybe (like the Disney Store and the Warner Bros. Store) it's time for Marvel and DC to open (owned and operated or franchised) their own chain of comic specialty stores! Think about the possibilities!

The comic book specialty stores provide the casual and serious reader of graphic literature with a positive atmosphere to discover and purchase comics. Store owners and staff are generally very knowledgeable about a wide range of titles and related subjects and are alert to trends in stories. If they notice a buyer is interested in certain types of titles, he or she is more likely to suggest other titles which are related. Publishers benefit by only publishing books which they know are going to be sold. Costly over-runs are virtually eliminated.

.

4. Compensation

Unequivocally, comic book artists and writers must have creative freedom. In order to provide new concepts, stories and art, this freedom should be vigorously encouraged by all comic book publishers and enhanced by an equitable and competitive compensation system.

Employee Compensation Specialists routinely conduct salary surveys with a variety of employers to determine competitive salaries and other methods of compensation. How do the salaries and other methods of compensation of comic book writers and artists compare with those of screenwriters, novelists and commercial artists? For example, Roy Thomas' decade-spanning work as primary writer of Marvel's "Conan" property is legendary. However, John Milius and Oliver Stone co-wrote the screenplay for the film, "Conan the Barbarian" and, very likely were paid far in excess of Thomas' annual salary at Marvel. Hopefully, Thomas, as screenwriter for the sequel, "Conan the Destroyer" was paid - equitably. Of course, in some instances there are no legitimate comparisons. However, where legitimate comparisons do exist, comic book professional should be compensated equitably.

.

5. Self-Regulation

Jan Strnad in Comic Scene No. 10: "The comic book morality crisis is not far off. . . . I propose that we act now, while we can still do so, simply and effectively, without outside interference."

Dick Giordano in response to Strnad in Comic Scene No. 11: "I really don't agree with Jan Strnad on this point at all. The Comics Code was not a dumb idea in the '5Os. . . . it saved the comics industry. And although that Code might be a dumb idea now, a new Comics Code would work wonders if it were conceived and administered in a well-planned, thoughtful and dynamic fashion. This would actually be easier to do than (implementing Jan's proposal of) adapting the movie rating system. The apparatus is already in place. All it needs to really start functioning is an influx of new blood. . . the newer publishers."

Should Warren's 1994, Richard Corben's Jeremy Brood and even Pacific's Twisted Tales (despite its recent "Recommended For Mature Audiences" disclaimer) be on the same magazine racks with obviously adolescent-oriented books such as Captain Carrot, GI Joe, US 1 and Red Circle's Katy Keene? Do your really think that Frank Thorne, Bruce Jones, Richard Corben, Jim Starlin and Walt Simonson have 10 and 12 year olds in mind when they are plotting or illustrating their stories? I've only touched on this lightly before, but again, the term "comic" has very little to do with "comic books".

The industry really grew up and out of that label through some of the original EC stories and particularly with the dawn of the Fantastic Four and the "Marvel Age". For almost 20 years, comic book writing has become progressively more serious and more complex. Things just don't "happen" in comic book stories anymore. Nowadays, things must be scientifically, logically, and pragmatically explained with a stoic-like omniscience. If "comics" were all fun and games, do you honestly think that Marvel (and soon DC) would publish their most articulate and comprehensive "Handbook of the Marvel Universe?"

If you read comics (and obviously you do, or are about to, if you're reading this) then you know how serious you are about demanding explanations for how and why things happen in the books you read.

We who read comics know better than to label everything with words and pictures as "comical". As I see it, the comic book industry, fans and collectors must erase the stigma that comics have acquired over the years as being comical, frivolous, juvenile, trashy, stupid, gory, cheap and so forth. We must redefine and then re-educate the general public's perception of the comic book industry.

According to Giordano, DC has "...already decided on the basic elements of three separate and distinct cover formats to be utilized on titles targeted for three separate and distinct age group audiences." I agree with Giordano and with DC. Optimistically, the comic book industry could reach unparalleled success through a refurbished Comic Magazine Association of America and a refined marketing of "comic books" as "graphic literature" to specific audiences.

.

6. Public Relations

I am genuinely interested in promoting a positive image of the comic book industry. I've been recommending comics to people for years -- without using the "hard sell" technique. Generally, once I've provided an adult (18-39 years old) with an Alien Worlds, Dreadstar, etc., I've found the stories and the characters sell themselves. In fact, most adults are surprised when I acquaint them with the depth of characterization and plotting that exists in so many titles.

Question: Who handles the public relations function for the comic book industry?

I really don't know the answer. I suppose each publisher has its own public relations function of some sort or another. The Comics Magazine Association of America provides an image" for the industry, but I wouldn't really say it functions in a commercial public relations capacity. There seems to be something lacking here.

To sell a more positive, mature image for the industry I suggest the following public relations tactics:

- Schedule appearances for comic book writers and artists on quality television (Hour Magazine, Donahue, The Tonight Show, etc.) and radio talk shows to talk about the new image of the comic book industry.

- Get 60 Minutes (CBS), 20/20 (ABC), White Paper (NBC) and the syndicated "Entertainment Tonight" to do features on the "new image" of the comic book industry. Have artists, writers, editors, collectors and others interviewed.

- If it has not been done already, lobby in Congress for a National Comic Book or National Comic Magazine Week. If "Superman" doesn't qualify as an icon for American values of truth, justice and liberty...who does?

- Routinely release comic book industry financial and personnel "happenings" to the Wall Street Journal, Fortune, Forbes, Money, Time, INC, US News and World Report and other mainstream magazines.

- Establish a working relationship with text book publishers and with school districts throughout the United States in hopes of developing educational products, text books, and curriculum for specific audiences (elementary through college and graduate school levels).

- Provide television and radio game shows with comic books for contest prizes and give-aways (i.e., "A promotional fee has been paid by Marvel Comics).

- Advertise comic books in the other media: newspapers, magazines, radio, and television, including cable.

- Have a comic book day" at ball parks throughout the nation, similar to the ever-popular "bat day."

- Acquire celebrity endorsements. For instance, imagine these 30 second TV ads:

Clint Eastwood saying, "I read the X-Men. Don't you?"

Jack Palance saying, "I read Twisted Tales. Don't you?"

Larry Holmes and Chuck Norris saying, "We read Power Man and Iron Fist: Don't you?"

10. Teach, train, instruct, orient, and thoroughly "showcase" the synergy" of comic book art and writing and all related production aspects to K-12 students, colleges and universities, graphic and fine artists, and especially film producers, directors, screen writers, and special effect technicians.

CLICK ABOVE IMAGE FOR MORE INFORMATIONThrough the speakers bureau of a former employer, I was able to inform and educate many people from elementary students to members of civic organizations about the comic book industry. I found then, as I do now, that most people don't understand mainstream comics. I generally try to explain how comics are produced (written, drawn, inked, etc.), printed (manual color separations, World Color Press), sold (direct sales vs. newspaper stands) and why each comic book publisher develops their own marketing style.

Lobbying for the comic book industry at a national level does not seem to exist. Clearly, the intention here is not to benefit any one company but to benefit the comic book industry at large. Someone to meet with and talk to schools, politicians, churches, the media, political and civic action groups, and just about anybody who will listen.

Click above image to review/download brochure

.

SUMMARY

Sure there are hundreds of ways to promote the comic book industry. In order to improve the industry's image though, the general public must be informed that there is more to comics than just Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Spider-Man and the Hulk. So many changes are occurring within the comic book industry, and in the ways that books are being published. People need to know. You and I know what's going on, but "they" don't.

Hopefully, one day soon the comic book publishers will begin the process of "legitimizing" the medium. The ideas I have suggested can be most effective if there is complete support by all publishers to improve the image of comic books.

Comics are not just for kids anymore. As a literary form, comics should be for everyone. Have you read the latest issue of Dreadstar? Well, let me tell ya...

.

Epilogue, 2000

It's now 2000, and while so much has changed with comics, sadly, so much remains the same. Oh, I still collect but nearly seven (7) years ago I dramatically reduced my collecting practices. Why? Essentially, the industry had become less innovative, less creative. In fact, I know of many collectors at my former level who also grew tired of the continued mediocrity in mainstream comics. Again, how many X-men titles are necessary? How many times and ways does Superman have to be killed in a pathetic attempt to punch life into an American icon? When compared to the greater acceptance of comics and anime by adults in Europe and Asia, where's the corresponding evolution in the United States?

After reading the January/February 2000 issue of Cinescape Magazine, page 10 and 11, I decided to dust off my admittedly subjective letter which I sent to both Marvel and DC comics back in 1983. According to Cinescape, "While consumers were buying 50 million comic books a month back in 1993 (around the time I was reducing my collecting practices), today they only buy about 8 million copies a month. As usual, comic book industry officials like Dark Horse president Mike Richardson make excuses and this time point to "...the Internet generation" in addition to television, movies and video games for competing for young people's attention. He just doesn't get it. I'll send him a copy of this paper.

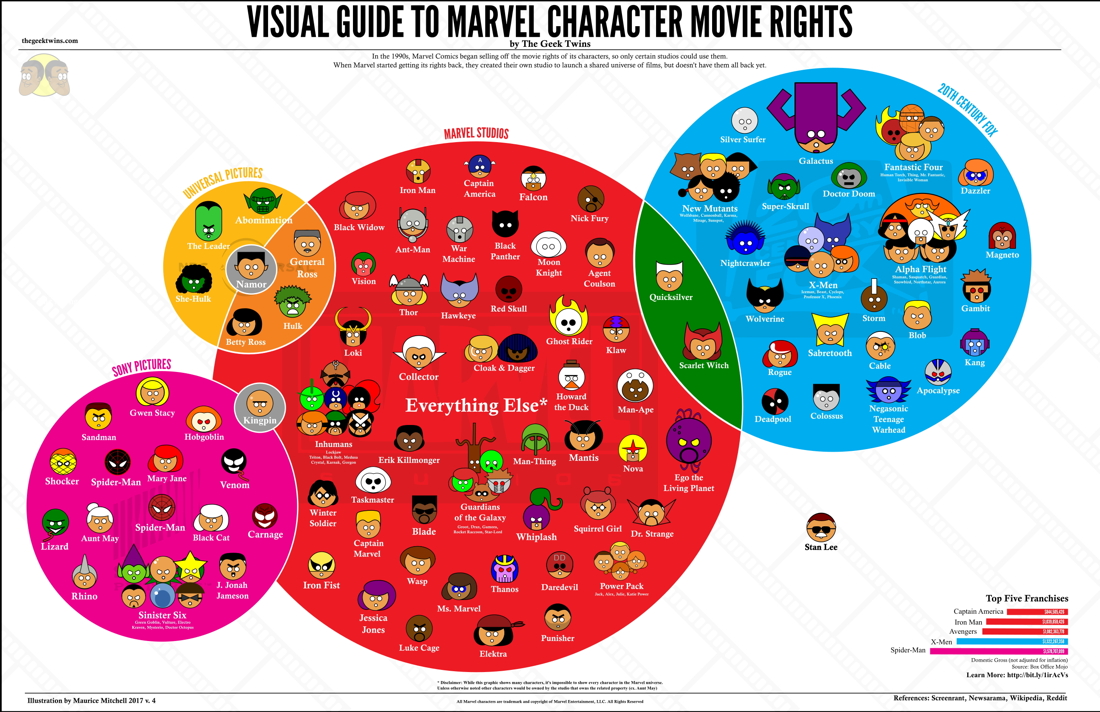

As with the release of Michael Keaton's first "Batman" and Christopher Reeve's first "Superman" film, very soon, yet again, in conjunction with the release of "The X-men" and later the long awaited "Spider-man," the buzz will go out about these very successful comic books. So many filmed projects are planned including "Superman V" maybe with Nicholas Cage, "Iron Man" and many more. Licensing content (see graphic below) is not an original idea; in fact, prior to being purchased by Disney, Marvel Comics licensed many of its characters to Sony, Fox, and Universal. However, in 2009 Disney purchased Marvel and subsequently purchased Fox, and now has ownership and total control of "all" Marvel properties. Keep in mind, just like China only "leased" Hong Kong to the United Kingdom for ninety-nine-(99) years, Marvel only "licensed" its content, it did not "sell" anything.

Unfortunately, this is business as usual for Hollywood to generate revenue and profit to benefit the film industry, but historically, without providing a corresponding strategic plan to increase and sustain the "customer base" specific to the original source material, specifically, the comic book industry. Case in point, the collective revenue generated by Disney's Marvel Studios film franchise ($15,664,965,624), see exhibit below, overwhelmingly dominates the revenue produced by all studios represented in the Top 50 films of all-time. Warner Bros. Discovery's DC superhero franchise is a distant second at $3,304,156,500. By the way, twenty-eight-(28) or 56% of the Top 50 highest grossing films of all-time belong to Disney!

| Rank | Title | Studio | Distributor | Worldwide Gross (Billions) | Year | Disney | Warner Bros | Universal | Paramount | Others |

| 1 | Avatar | 20th Century | 2,923,706,026 | 2009 | 1 | |||||

| 2 | Avengers: Endgame | Disney / Marvel | Disney | 2,797,501,328 | 2019 | 1 | ||||

| 3 | Avatar: The Way of Water | 20th Century | 2,320,250,281 | 2022 | 1 | |||||

| 4 | Titanic | Paramount | 2,257,844,554 | 1997 | 1 | |||||

| 5 | Star Wars: The Force Awakens | Disney | 2,068,223,624 | 2015 | 1 | |||||

| 6 | Avengers: Infinity War | Disney / Marvel | Disney | 2,048,359,754 | 2018 | 1 | ||||

| 7 | Spider-Man: No Way Home | Disney / Marvel | Disney | 1,921,847,111 | 2021 | 1 | ||||

| 8 | Jurassic World | Universal | 1,671,537,444 | 2015 | 1 | |||||

| 9 | The Lion King | Disney | 1,656,943,394 | 2019 | 1 | |||||

| 10 | The Avengers | Disney / Marvel | Disney | 1,518,815,515 | 2012 | 1 | ||||

| 11 | Furious 7 | Universal | 1,515,341,399 | 2015 | 1 | |||||

| 12 | Top Gun: Maverick | Paramount | 1,495,696,292 | 2022 | 1 | |||||

| 13 | Frozen II | Disney | 1,450,026,933 | 2019 | 1 | |||||

| 14 | Barbie | Warner Bros. | 1,445,638,421 | 2023 | 1 | |||||

| 15 | Avengers: Age of Ultron | Disney / Marvel | Disney | 1,402,809,540 | 2015 | 1 | ||||

| 16 | The Super Mario Bros. Movie | Universal | 1,361,992,475 | 2023 | 1 | |||||

| 17 | Black Panther | Disney / Marvel | Disney | 1,347,280,838 | 2018 | 1 | ||||

| 18 | Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 | Warner Bros. | 1,342,139,727 | 2011 | 1 | |||||

| 19 | Star Wars: The Last Jedi | Disney | 1,332,539,889 | 2017 | 1 | |||||

| 20 | Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom | Universal | 1,308,473,425 | 2018 | 1 | |||||

| 21 | Frozen | Disney | 1,290,000,000 | 2013 | 1 | |||||

| 22 | Beauty and the Beast | Disney | 1,263,521,126 | 2017 | 1 | |||||

| 23 | Incredibles 2 | Disney | 1,242,805,359 | 2018 | 1 | |||||

| 24 | The Fate of the Furious | Universal | 1,238,764,765 | 2017 | 1 | |||||

| 25 | Iron Man 3 | Disney / Marvel | Disney | 1,214,811,252 | 2013 | 1 | ||||

| 26 | Minions | Universal | 1,159,444,662 | 2015 | 1 | |||||

| 27 | Captain America: Civil War | Disney / Marvel | Disney | 1,153,337,496 | 2016 | 1 | ||||

| 28 | Aquaman | Warner / DC | Warner Bros. | 1,148,528,393 | 2018 | 1 | ||||

| 29 | The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King | Warner Bros. | 1,147,997,407 | 2003 | 1 | |||||

| 30 | Spider-Man: Far From Home | Disney / Marvell | Disney | 1,131,927,996 | 2019 | 1 | ||||

| 31 | Captain Marvel | Disney / Marvel | Disney | 1,128,274,794 | 2019 | 1 | ||||

| 32 | Transformers: Dark of the Moon | DreamWorks | 1,123,794,079 | 2011 | 1 | |||||

| 33 | Skyfall | Sony / MGM | 1,108,569,499 | 2012 | 1 | |||||

| 34 | Transformers: Age of Extinction | Paramount | 1,104,054,072 | 2014 | 1 | |||||

| 35 | The Dark Knight Rises | Warner / DC | Warner Bros. | 1,081,169,825 | 2012 | 1 | ||||

| 36 | Joker | Warner / DC | Warner Bros. | 1,074,458,282 | 2019 | 1 | ||||

| 37 | Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker | Disney | 1,074,144,248 | 2019 | 1 | |||||

| 38 | Toy Story 4 | Disney | 1,073,394,593 | 2019 | 1 | |||||

| 39 | Toy Story 3 | Disney | 1,066,970,811 | 2010 | 1 | |||||

| 40 | Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest | Disney | 1,066,179,747 | 2006 | 1 | |||||

| 41 | Rogue One: A Star Wars Story | Disney | 1,057,420,387 | 2016 | 1 | |||||

| 42 | Aladdin | Disney | 1,050,693,953 | 2019 | 1 | |||||

| 43 | Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace | Disney | 1,046,515,409 | 1999 | 1 | |||||

| 44 | Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides | Disney | 1,045,713,802 | 2011 | 1 | |||||

| 45 | Jurassic Park | Universal | 1,037,535,230 | 1993 | 1 | |||||

| 46 | Despicable Me 3 | Universal | 1,034,800,131 | 2017 | 1 | |||||

| 47 | Finding Dory | Disney | 1,028,570,942 | 2016 | 1 | |||||

| 48 | Alice in Wonderland | Disney | 1,025,468,216 | 2010 | 1 | |||||

| 49 | Zootopia | Disney | 1,023,784,195 | 2016 | 1 | |||||

| 50 | The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey | Warner Bros. | 1,017,030,651 | 2012 | 1 | |||||

| Disney / Marvel | $15,664,965,624 | Number | 28 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 50 | ||

| Warner / DC | $3,304,156,500 | Percent | 56 | 14 | 16 | 6 | 8 | 100 | ||

Oh, don't get me wrong, I love movies (http://tripoetry.com/Film/filmreviews.htm) and, in particular, the filmed adaptations of comic book properties. Here are a few of my film reviews.

| The Eternals | SHANG-CHI and the Legend of the Ten Rings | |

| http://tripoetry.com/Film/Reviews/Eternals.htm | http://tripoetry.com/Film/Reviews/Shang-Chi.htm | |

| Black Widow | Black Panther | |

| http://tripoetry.com/Film/Reviews/Black-Widow.htm | http://tripoetry.com/Film/Reviews/Black_Panther.htm | |

| Spider-Man: Home Coming | The Fantastic Four | |

| http://tripoetry.com/Film/Reviews/Spider-Man-Homecoming.htm | http://tripoetry.com/Film/Reviews/FF.htm | |

| Guardians of the Galaxy | Captain America: Winter Soldier | |

| http://tripoetry.com/Film/Reviews/Guardians-Galaxy.htm | http://tripoetry.com/Film/Reviews/Captain-American-Winter.htm |

Yet, I like to read too!

In 1983, I had the vision to suggest that Marvel and DC open a chain of comic specialty stores (owned and operated or franchised) of their own. Later, between 1987 and 1989 there was a major comic book specialty store owner in Dallas-Fort Worth, Texas who publicly disagreed with what he perceived as objectionable subject matter in many DC titles. He also admitted his objective to do whatever he could to put DC Comics out of business. In fact, for the better part of a year he directed his employees that under no circumstances should a DC Comic or related merchandise be a "featured" item - no matter how hot that DC property might be. The exception? Two weeks before the release of the "Batman" movie his stores began featuring the many "Batman" movie tie-ins, collectibles and gifts. Clearly, while individual First Amendment rights are critical, nevertheless, the "business" of comics remains the essential reason for the existence of the industry!

In 1989, I wrote DC regarding the possibility of establishing exclusive retail outlets (ERO). DC thanked me for the idea but elected not to pursue the retail business then or in the foreseeable future. Okay, EROs was just one idea and maybe not the most practical. However, in the seventeen (17) years that have passed since I wrote the original paper, with few exceptions, Marvel and DC continue to manage the industry as though it's the 1950s.

As I said in 1983, I've demonstrated I can and will support the comic book publishing industry where it counts - by buying books! That's right, I'm a customer. Unfortunately, the comic book industry doesn't share my vision of customer service or, sadly, how to develop and expand markets. That's a shame.

Epilogue, 2024

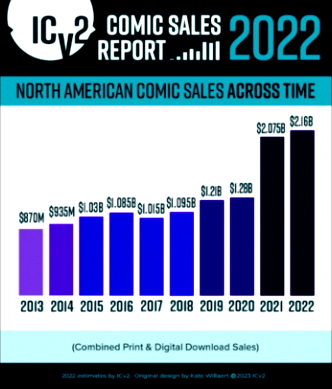

It's now 2024, and much has changed with comics, kinda. Did you know, as reported by Comichron, the world's largest public repository of comic-book sales figures, featuring data from the 1930s to today, sales of comics and graphic novels grew over 60% in 2021, according to a new joint estimate by ICv2's Milton Griepp and Comichron's John Jackson Miller. Total comics and graphic novel sales to consumers in the U.S. and Canada were approximately $2.075 billion, a 62% increase over sales in 2020, and up over 70% from sales in 2019. “Publishers made more selling comics content than in any year in the history of the business, even when adjusted for inflation,” said Miller of the 2021 estimates.

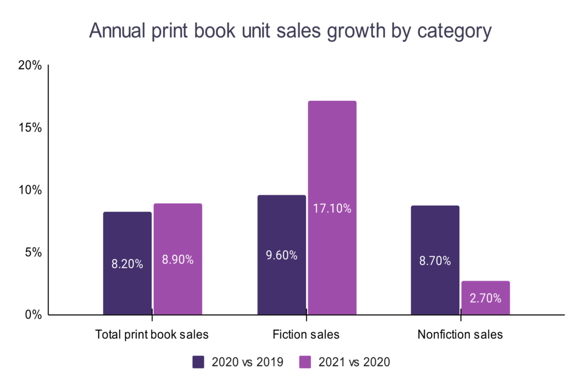

However, as reported by Wordsrated.com, collectively, all print book sales soared during the pandemic, even though physical stores had a hard time: In 2020, over 750.9 million print books were sold in the USA, representing an 8.24% increase over 2019.Given the achievements of computer generated content and special effects, as expected, the single greatest impact on the comic book industry has NOT been to propel a greater interest in comics by actually "promoting the reading of comic books," but to watch comic-related-product from Disney's Marvel Cinematic Universe or Warner Bros. Discovery's DC Cinematic Universe via traditional movie theatres, broadcast and cable television, or streaming devices (home internet, smart phones, etc.). Clearly, in the wake of COVID-19 the aforementioned multimedia platforms will rebound, which will again result in lower profits from the comic book industry's business-as-usual revenue streams. There's nothing "comical" about a lack of ingenuity, an absence of creativity, and constantly labeling your name, image, and likeness as "comic."

Case in point, "Apple Computer" evolved from being a manufacturer of computer hardware and software to become simply, "Apple," the world's leading manufacturer of "consumer electronic products."

Marvel and DC, wake-up.

Trip Reynolds, Comic Book Collector

and Subject matter expert in human capital management (job design, organizational development, etc.)

© 1983 - 2003 by Trip Reynolds

For presentations, click here.